COP26: The Outcomes

What Has Been Achieved at the COP26 Conference and Is It Enough?

By Frankie Lloyd

After almost two weeks of negotiations regarding the global response to climate change, the 26th Conference of the Parties concluded on Saturday the 13th of November. The Glasgow conference - which was the first ever to admit that fossil fuels directly cause climate change - saw nations pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and keep the rising global temperatures below 1.5℃. However, whilst promising agreements have been made, many are left feeling discouraged and disappointed following COP26. Leaders failed to agree on the crucial measures for steering the world away from climate disaster, despite a stirring call to action from António Guterres (UN Secretary General), who attempted to inspire with the phrase: ‘it's time to go into emergency mode or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero’.

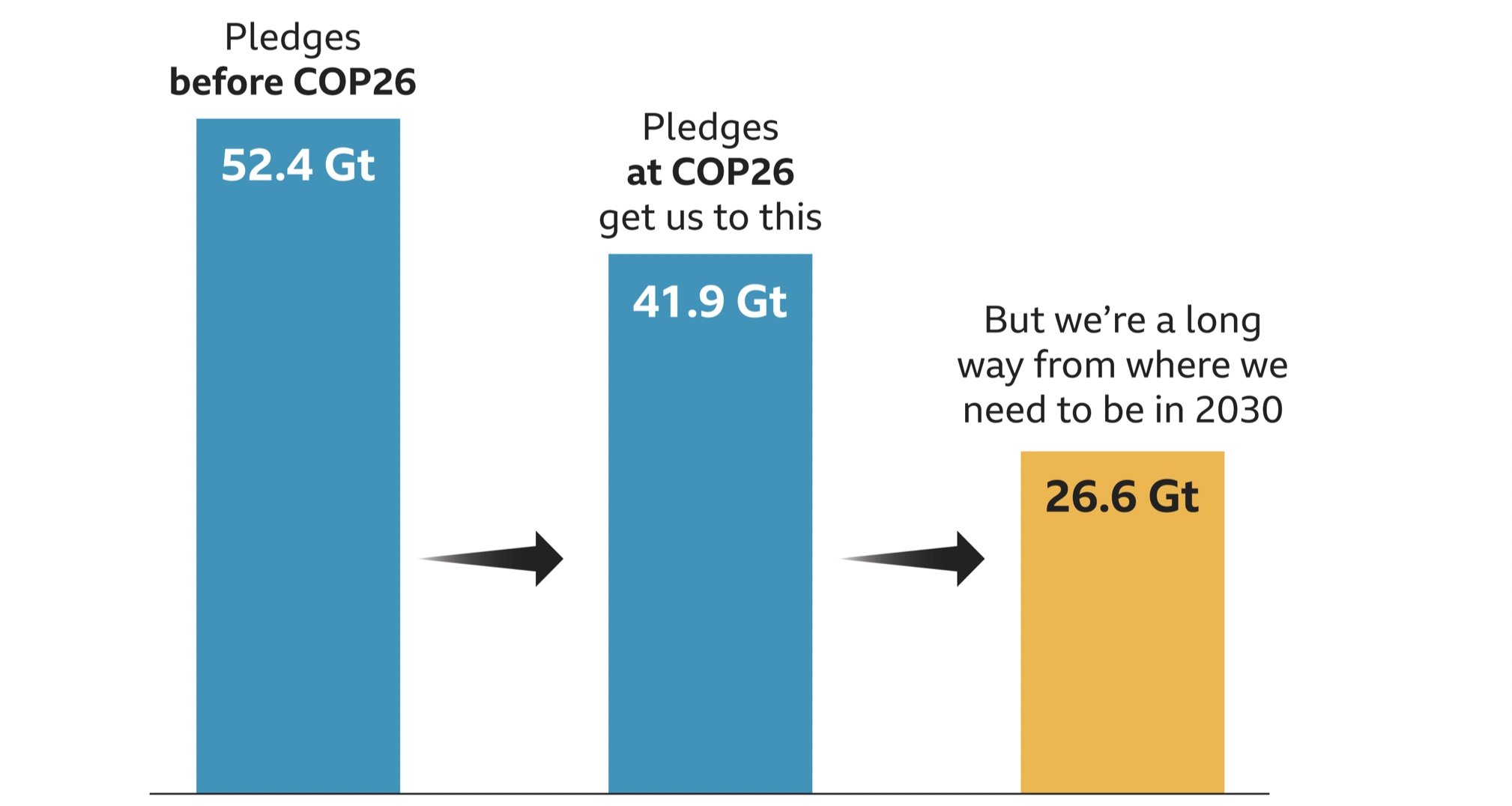

The Energy Transitions Commission recently released data explaining that before COP26, the world was on track to release 52.4 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases by 2030. Following COP26, the Commission says that this number could reduce to 41.9 gigatonnes if commitments are adhered to. On the surface, this appears to be promising. However, to keep global temperature rises at 1.5℃, we would need to limit emissions to 26.6 gigatonnes. This shows that COP26 negotiations have not gone far enough in responding to the global climate crisis we are facing.

The Energy Transitions Commission projected greenhouse gas emissions by 2030

In the first major deal of the event, more than 100 countries vowed to reduce deforestation and methane emissions by 2030 - a promising pledge and a move welcomed by experts. With over 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide, methane is a significant greenhouse gas and reductions in its emissions are crucial in tackling the climate crisis. Additionally, trees are a natural carbon capture and storage system — removing carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and replacing it with oxygen. Deforestation removes these trees from our land, reducing the volume of carbon that can be uptaken via these natural processes.

Conclusions regarding the use of coal have left many disheartened. Whilst we celebrate victories from countries including Poland, Vietnam and Chile promising to shift away from coal use, others are hesitant to take the pledge. COP26 initially aimed to ‘phase out’ unabated coal use, but last minute changes to the agreements transformed the pledge’s wording into a promise to ‘phase down’ coal use. This change was proposed by India and China, who do not envision the complete phasing out of coal in their countries in the near future.

At the moment, 70% of India’s energy comes from coal. Bhupender Yadav, India’s climate minister, asked how his country could consider phasing out coal and fossil fuels whilst still prioritising economic development and the eradication of poverty. India’s coal industry provides almost 500,000 jobs which help reduce the rates of poverty amongst its citizens. There are fears that these jobs could be lost with the phasing out of coal. Simultaneously, Delhi is experiencing hazardous air quality conditions that have resulted in school closures and the consideration of lockdowns. It is clear to see that there is a need to offer capacity-building solutions to countries like India, allowing a prosperous industry to replace the coal industry and continue to provide hundreds of thousands of jobs for citizens.

Sumitmpsd, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

During the opening days of COP26, India also announced plans to become carbon neutral by 2070. Whilst positive, these plans contain a deadline twenty years later than other countries’ net zero strategies. This may very well be too late. Despite these below satisfactory developments, Vaibhav Chaturvedi from the Council on Energy, Environment and Water reminded the world that India still has plans to move to solar power. He stated that India’s transition to solar power will grow very quickly over the next decade whilst coal use will grow very slowly. It is also important to consider the carbon footprint of citizens in India, as the average individual will have a carbon footprint drastically lower than each person living in the global North, which poses questions of responsibility.

The final Glasgow agreements emphasised the need for developed countries to increase their climate funding beyond the 100 billion dollar target previously decided upon during the 2015 Paris Climate Accords. Additionally, around 450 financial organisations (who collectively control around 130 trillion dollars) have vowed to invest in clean, renewable technologies and to direct finance away from the fossil fuel industry. North America and Western Europe also pledged to stop financing overseas fossil fuel projects within the next 12 months. However, with COP26 agreements not legally binding, there is uncertainty surrounding whether these critically important developments will be adhered to.

For many of the young climate and environmental activists, the event has been a disappointment. Despite efforts to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5℃, the world is still believed to be headed to a 2.4℃ temperature increase compared to pre-industrial levels. This kind of temperature increase will raise sea levels, reduce crop yields, disrupt tens of thousands of homes, increase the frequency of natural disasters, and produce an unprecedented number of climate refugees. As young people demand a system change to tackle the climate crisis, global leaders have discussed nothing of the sort. Climate justice has been used as a buzzword in many COP26 speeches, yet it was rarely discussed within negotiation conversations, leaving guest activists from the heart of the climate crisis feeling ignored and undervalued.

As a result of the COP26 agreements, each country must produce a public climate action plan within the next 12 months. Only once these agreements are published will we truly know how far countries are willing to go to remediate the climate crisis and protect the lives of the vulnerable communities suffering at the hands of climate change. The next Conference of the Parties will take place in Egypt in 2022 and will give parties the opportunity to return to the negotiation table with updated national plans for tackling greenhouse gas emissions. However, as COP26 was not successful in finalizing these negotiations, many fear that COP27 will not result in concrete solutions to this dire climate situation.

With global leaders failing to deliver the actions many scientists, activists, and academics plead for, it is now more important than ever to value the power of science and technology and work together to form collaborative, community-based solutions. Whilst governments continuously delay impactful climate agreements, communities in low- and middle-income countries cannot delay the damage that is happening to their towns and homes. Cross-disciplinary solutions are needed and here at Environment Care, we are committed to working together to resolve the unjust issues impacting vulnerable communities in low- and middle-income countries. Pollution from the global north has pioneered their suffering, so it is the moral responsibility of the global north to contribute to and facilitate solutions that will improve the quality of life for millions of people. To quote António Guterres, “The COP26 outcome is a compromise, reflecting the interests, contradictions, and state of political will in the world today. It is an important step, but it is not enough”.

Frankie Lloyd

Environment Care Project Officer

f.lloyd@bham.ac.uk

Follow Our Socials for More Information and Updates